What is the Dunning-Kruger Effect?

The Dunning-Kruger Effect is when a person’s lack of knowledge and skills causes them to overestimate their own knowledge or ability in a specific area. This occurs because their lack of self-awareness prevents them from accurately assessing their abilities. This effect also causes those who excel in a particular task to believe others find the task simple as well.

The only true wisdom is in knowing you know nothing.

—Socrates

Understanding the Dunning-Kruger Effect

Cornell University psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger detailed this concept in their 1999 paper. In their study, the pair tested participants on their logic, grammar, and sense of humor and found something fascinating:

Those who scored in the bottom 25% overestimated their ability and test scores. Most predicted their scores to be in the top 60%!

Those who overperformed in the top 25% also incorrectly assessed their results. Most of these students estimated their scores to be lower, in the 70th to the 75th percentile range. But most actually scored above the 87th percentile.

The research suggested that people blissfully underestimate their lack of abilities in social and intellectual domains. The authors said the overestimation comes from a dual burden. Not only do these people reach erroneous conclusions and make unfortunate choices, but they cannot analyze their own thoughts and performance.

What Causes the Dunning-Kruger Effect?

Dunning and Kruger identified two significant components that were responsible for causing this miscalibration in thinking:

- Lack of skill or knowledge in a particular field of topic. They are incompetent in the area they think they are skilled in.

- Lack of metacognition. Simply put, metacognition is the ability to be aware of or understand one’s thought processes.

Essentially, these two things lead to a gap between perceived and actual performance and outcomes. Interestingly enough, as the skills of participants increased, so did their metacognitive competence, which helped them recognize the limitations of their abilities.

Who is Affected by the Dunning-Kruger Effect?

Most people are misinformed to some degree about their level of expertise, but the Dunning-Kruger effect affects those who lack knowledge and skills more often because they don’t know what they don’t know.

Five studies looked at the Dunning-Kruger Effect in real-world examples and found them in these situations:

- College students taking a test

- Medical students assessing their interview skills

- Clerks assessing their job performance

- Lab technicians speaking about their skills

In the workplace, this can look like candidates who are confident but unqualified for their position and confident employees who are not top performers but get an undeserved raise.

You might guess that overconfidence is more common in youth as well. However, one study specifically looked at how the various types of confidence correlate to age and did not find any evidence of overestimation or over-placement. However, they found evidence that precision in judgment increases with age.

Even smart people can mistakenly believe their intelligence on one topic is transferrable to another. And this isn’t the case. Being smart is not the same as developing skills and experiences that apply to all areas.

The movie Catch Me If You Can, based on the true story of Frank Abagnale, perfectly exemplifies the Dunning-Kruger Effect. Abagnale, played by Leonardo DiCaprio, was a young con artist who passed as a doctor, lawyer, and pilot at 21. The secret of his success—confidence.

5 Signs You Might Be Experiencing the Dunning-Kruger Effect

Have you ever heard similar feedback from others about how you disregarded them or ignored their input? Are there areas where you feel 100% confident? Do you find yourself uninterested in personal growth? You might experience the Dunning-Kruger Effect.

Unwillingness to learn

While each person has special abilities, some assume they are better than others, and because of their overconfidence, they don’t think they need to learn new things. In a workplace, you can often spot these individuals as individuals who blame their managers or the company for issues, suffer in finding jobs because their skills have not kept up with the market, and have low productivity.

Inaccurate time estimations

Overconfidence can lead to the inability to forecast timelines and then complete tasks on time. It can lead a person to believe they can finish a project or tasks in a shorter timeline than what is accurate. Then, based on the incorrect estimation, the person falls behind, and the project is delayed.

Overestimating abilities

Do you overestimate what you can do, only to have it lead to disastrous results? This might look like a person who signs up for a marathon and expects to run it without training or deciding to start a business on a whim, with no leadership skills or entrepreneurial abilities.

While it’s always great to believe in yourself and dream big, if you often wrongly overestimate your knowledge or ability, you might want to look at why this is happening.

Overestimating your memory

As a student, did you read the material once and expect you’d be able to recall it for the test? But when you got your test score back, you found out you bombed it?

Or do you run through a presentation once, thinking that’s all you need to do to prepare? But when the time comes to give it, you fumble over the words and concepts. This could be because you’ve overestimated your ability to remember the material.

Overestimating knowledge

Google has distorted the way people think about their own knowledge versus knowledge found on the internet. One study concluded that using Google artificially inflates people’s confidence in their own ability to remember and process information. This leads to erroneously optimistic predictions about knowledge. In short, people cannot recognize where individual knowledge ends, and Google knowledge begins.

Assuming You’re An Expert

Individuals who have had success in the past may mistakenly believe that this means they are an expert in a field. This may happen with a new investor who finds success in the stock market with their initial investment or a player that wins their first game. Instead of recognizing this as a small sample size of experience, a person with the Dunning-Kruger Effect may believe that they are an expert.

Why People Think They Know More Than They Do

Society highly values confidence, so much so that people would rather pretend to be educated and skilled rather than look incompetent.

Most people can relate. Can you think of a time you made up an answer instead of honestly stating that you didn’t know just to avoid being perceived as incompetent?

According to a significant study by Carnegie Mellon University, a professional’s confidence is more important than that professional’s reputation or skill set. So instead of validating the person who is honest about not knowing an answer, people who lack knowledge try to make up for it by having confidence.

Pro Tip: Want to learn how to make people like you? It’s not what you think.

Ask for advice, share a vulnerability, or admit a weakness—these actions bond you to people. This is called The Franklin Effect, and you can learn more about this technique along with hundreds of others in Captivate, The Science of Succeeding with People.

Three Flavors of Overconfidence

Overconfidence comes in three specific flavors—overprecision, overestimation, and overplacement. Their differences are nuanced and complex.

Overprecision is a person’s excessive faith that they are right. This may be as simple as being convinced you failed an exam when you passed. Or it may lead a gambler to believe they can accurately judge what card will appear next, leading to risky behavior and huge losses.

Research shows this bias increases with age.

They reported, “This result contradicts the proposition that a lifetime of experience, and of being wrong, would dampen the bold claims of confidence to which so many of us are prone. Instead, in this case, it appears that older people are more likely to claim that they know the truth. Nevertheless, the implications of the findings are potentially significant. If people’s confidence in the accuracy of their beliefs increases with age, then we might expect that people become more set in their beliefs, more ideologically extreme, and more resistant to persuasion as they age.

Overestimation is a person’s thinking that they are better than others or more proficient at a task than they actually are. Sometimes those who overestimate themselves underperform in jobs for which they aren’t qualified or take risks because they don’t recognize the limits of their abilities.

An example of this would be someone who tries out for a talent show but lacks talent or this yoga enthusiast who broke 110 bones while attempting a stunt from her balcony on the 82nd floor. Or the pilots who attempted to swap planes mid-air but ended up with revoked licenses and one crashed plane.

Researchers are unsure about why people overestimate. Some have considered wishful thinking as a self-serving bias that leads to overconfidence and positive attitudes, which leads to better performance.

However, other findings note that it varies based on the difficulty of the task. When a job is easy, people tend to underestimate performance, but if the task is more complex, they tend to overestimate their performance. The powerful influence of task difficulty and the commonness of success is known as the hard-easy effect.

For example, if you ask people to estimate their chances of surviving the flu, they will radically underestimate this high probability. But if you ask smokers about their chances of getting lung cancer, they will dramatically underestimate the likelihood of receiving this terrible diagnosis.

Overplacement is a person’s exaggerated certainty or belief that they are better than others or have more knowledge or skills. Researchers assess it with questionnaires that ask participants to note their level of certainty with a percentage.

An American psychologist, Justin Kruger, said that this effect is more often seen in simple tasks in which people feel competent and can quickly achieve success; however, if the task is difficult, the effect gets reversed, and the people believe themselves as less competent than others.

Overplacement occurs most frequently in people with low abilities who cannot assess their skill level accurately.

It is often associated with narcissistic behavior because confident people are better at deceiving others. This study found that individuals who rated themselves higher were rated higher by others, irrespective of their actual performance.

The authors said, “Overconfident individuals are overrated by observers, and underconfident individuals are judged by observers to be worse than they actually are…The findings suggest people may not always reward the more accomplished individual but rather, the more self-deceived.”

Let’s look at a scenario where all three are in play and then break them down.

Let’s say you take a pre-interview exam and confidently believe you scored above 90% of people, performing better than most of the applicants. But, in fact, you received a 70%, scoring in the middle of the group., In this case, you’d demonstrate overestimating, overplacement, and overprecision simultaneously.

The overestimation is guessing a score above your actual score. The overplacement comes from the thought you did better than the rest of the applicants, and overprecision is being too confident that your estimate is appropriately regulated.

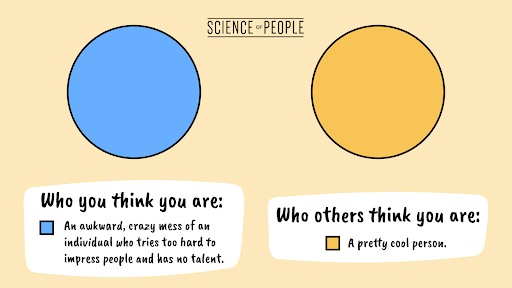

The Opposite of the Dunning-Kruger Effect: Imposter Syndrome

The polar opposite of the Dunning-Kruger Effect is imposter syndrome. Impostor syndrome is a psychological phenomenon in which you feel you don’t deserve your accomplishments and fear being exposed as a fraud. You might feel you don’t belong, don’t deserve your success, or are “out of place.”

Learn more about The 5 Types of Imposter Syndrome (And How to Overcome It!).

4 Tips to Minimize the Dunning-Kruger Effect

You can make progress in overcoming the Dunning-Kruger Effect through self-awareness. Self-awareness is the ability to evaluate whether your words, actions, and thoughts match your ideals. It means that besides being able to think, an individual cultivates the ability to think about what they’re thinking.

- Question what you know. Are there things about yourself or the world that you think you know or have always believed in and never questioned? Assessing the origins of these thoughts can help you become more open to new or different ideas and listen to other’s viewpoints.

- Be open to feedback. While feedback can feel threatening, it can also provide a path toward personal growth and improvement. Take time to reflect on your actions and performance before making a judgment on whether the other person is wrong.

- Become a life-long learner. Be willing to learn new skills and improve the ones you have through a coach or mentor. Look for someone who is slightly ahead of you in your professional life, or opt for a coach who can help you improve your life skills.

- Realize your unconscious biases. Understand the nature of your biases through an evidence-based test. Harvard offers several free Implicit Association Tests to better understand where you may have biases.

Read our full guide on self-awareness and how to cultivate it here.

Crack The Code on Facial Expressions

The human face is constantly sending signals, and we use it to understand the person’s intentions when we speak to them.

In Decode, we dive deep into these microexpressions to teach you how to instantly pick up on them and understand the meaning behind what is said to you.

Don’t spend another day living in the dark.