Have you ever desperately wanted to feel closer to your partner, but they pushed you away once you pulled them towards you? Or, on the flip side, where you felt like things were going great, but as soon as you reached a new layer of intimacy, your partner suddenly seemed unbearably clingy?

If either of these situations feels familiar, you might have an insecure attachment style. In this post, we’ll break down exactly what that means and how to navigate relationships if you or your partner have this attachment style.

What Is Insecure Attachment?

The term “insecure attachment” refers to a category of attachment styles generally characterized by a lack of trust and a fear of intimacy, often resulting from unmet childhood needs. There are three primary types of insecure attachment styles: avoidant, anxious, and disorganized. About half of the adults1https://www.researchgate.net/publication/24440045_The_first_10000_Adult_Attachment_Interviews_Distributions_of_adult_attachment_representations_in_clinical_and_non-clinical_groups have an insecure attachment style.

The concept of insecure attachment comes from attachment theory, pioneered by psychiatrist and psychoanalyst John Bowlby2http://www.psychology.sunysb.edu/attachment/online/inge_origins%20DP1992.pdf in the 1950s. It is based on the premise that the type of bond that children have with their primary caregiver greatly influences their emotional health, social relationships, and perspective of the world as they grow.

There are many folks who want deep, intimate bonds, but whenever a relationship gets to a certain level of depth, things seem to blow up. While it may seem like they are exhibiting self-sabotaging behavior, it might actually be their insecure attachment patterns getting activated.

We’ll unpack this more as we go, but here are each of the three styles in simple terms:

Avoidant-Dismissive Attachment: Picture someone who really likes their personal space and freedom. They don’t open up to others easily and often keep their feelings to themselves. They might avoid getting too close or intimate with others because they fear it might trap them or make them lose their independence. Intimacy can feel overwhelming for these folks.

Anxious-Preoccupied Attachment: Imagine someone who often worries about their relationships. They might struggle with low self-worth and constantly fear that others don’t love them as much as they love others or that people will abandon them. They seek approval and reassurance from others, sometimes to the point of seeming needy or clingy. They also might struggle to find independence outside of the relationship.

Fearful-Avoidant Attachment: This one’s a bit trickier. Imagine someone who acts unpredictably in relationships. One minute they might want closeness; the next, they might push people away. This is because they struggle to trust others, often due to past experiences of being let down, hurt, or abused. They want to form close relationships but have deep trauma around emotional intimacy.

A note on verbiage

It’s a little confusing, but the verbiage for each pattern shifts from the childhood3https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3051370/ to the adulthood4https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Bartholomew-and-Horowitzs-1991-model-of-adult-attachment_fig1_275367267 version.

Anxious-avoidant children become avoidant-dismissive adults.

Anxious-ambivalent children become anxious-preoccupied adults.

Disorganized children become fearful-avoidant adults.

And secure children become secure adults.

Possible Causes of Insecure Attachment

Like all aspects of our personality, insecure attachment is partially due to our genetics and partly due to upbringing.

In fact, research estimates5https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8474999/#:~:text=shaped%20throughout%20development.-,Genetic%20research%20indicates%20that%20up%20to%2045%25%20of%20the%20variability,be%20explained%20by%20genetic%20causes. that about 40% of the variability in insecure adult attachment is due to genetics.

On the upbringing side, it’s believed that attachment styles may stem from early childhood relationships2http://www.psychology.sunysb.edu/attachment/online/inge_origins%20DP1992.pdf with caregivers. If a caregiver were inconsistent, emotionally unavailable, or even dangerous, the child would likely develop an insecure attachment style.

Many psychologists6https://www.psychalive.org/how-your-attachment-style-affects-your-parenting/ also believe that if a parent has an insecure attachment style, then this will inform how they connect with their child, and they will effectively “pass on” the attachment style.

For example, a parent with an avoidant attachment style may be emotionally distant from their child and create space between them. As a result, the child may internalize these avoidant tendencies and bring them into their future relationships.

If you’d like to better understand and influence relational dynamics, check out this goodie.

Become More Influential

Want to become an influential master? Learn these 5 laws to level up your skills.

To understand insecure attachment more deeply, let’s dive deeper into the fundamentals of attachment theory.

Attachment Theory 101

What is attachment theory?

Attachment theory is the idea that, as humans, we are all born with an innate need for love and affection from others. Depending on how attentive and empathetic our caregivers were to us as children, we developed different relationships to intimacy and to how we see the world.

Secure attachment provides a base for safety

Psychologist Harry Harlow conducted compelling research in the 1960s that planted the seeds for attachment theory. His research suggested that when a child attaches to a caregiver, the caregiver serves as a “base” of sorts. The caregiver is a source of comfort, affection, and safety that empowers the child to explore the world. Whenever the child feels afraid or uncertain, they can return to the base to calm their nervous system.

Except, Harlow’s research wasn’t with humans. He ran experiments with baby rhesus monkeys and “mother monkeys” made of steel. While the ethics of his research were questionable, we can still glean insights from his work.

In an experiment, Harlow separated baby monkeys from their mothers shortly after birth and raised them with two inanimate surrogate mothers: one was made of wire and equipped with a feeding bottle. At the same time, the other was covered in soft terry cloth but had no food.

He found that the infant monkeys spent significantly more time with the cloth mother than the wire one, even though the wire mother provided nourishment.

Harlow then spooked the baby monkeys with a terrifying and loud robot he built. When they saw the robot, the baby monkeys sprinted away to the cloth mother—not the mother with the feeding bottle—to find comfort. And after a few moments with the cloth mother, the babies felt soothed and then went on to growl at the robot.

Lastly, Harlow put the baby monkeys in an unfamiliar room with a bunch of objects and with no “mother” present. The monkeys were paralyzed and unable to explore. Even when he put a wire mother in the room, the babies were still unable to explore. It was only when a cloth mother was put in the room that the baby monkey cuddled with the cloth mother until it calmed down and then went on to explore the room. This pattern remained true even for babies “raised” exclusively by a wire mother for their first year of life.

The monkeys sought comfort from the cloth mother, especially when frightened or stressed, suggesting a preference for emotional comfort over mere sustenance. This led Harlow to conclude that attachment and affectional bonds are about more than just providing basic needs like food; comfort and emotional care are crucial to healthy development, and attachment figures can serve as a base to soothe and empower a child.

The baby monkeys could only function at their full capacity when there was a parent figure who could provide comfort. Humans, as we’ll soon see, might not be so different.

Check out actual footage from the experiment here:

Our attachment patterns emerge in infancy

Psychologist Mary Ainsworth pushed forward Harlow’s work with a human experiment called “The Strange Situation2http://www.psychology.sunysb.edu/attachment/online/inge_origins%20DP1992.pdf” in 1969.

In this experiment, researchers put a one-year-old toddler and their primary caregiver in an unfamiliar room neither of them had seen before, and sometimes there was a stranger in the room. The room was full of toys.

In the study, researchers would watch how the child would engage with the toys while the caregiver was nearby. After a few minutes, the caregiver would exit the room, leaving the child alone, and then return after a few more minutes. When the caregiver left, the children behaved in four notably different ways, which researchers then categorized as the four attachment types.

Let’s go over each of the four attachment styles below and how children of each style behaved in the strange situation test.

The four attachment styles

Secure attachment

Secure children grow up with caregivers who offer them empathetic support. When the child is sad or upset, the caregiver will usually mirror this emotion instead of trying to get the child to feel differently. As a result, these children feel safe with their caregivers.

In the Strange Situation test, securely attached toddlers were comfortable exploring their environment while the caregiver was present. They became upset when the caregiver left but were easily soothed upon their return, often seeking physical contact. After being comforted, they were usually willing to return to play, not dissimilar from the monkeys who felt soothed by their cloth mother.

The following three styles are the three types of insecure attachment styles.

Anxious-avoidant attachment

Avoidant children tend to have caregivers who are cold, aloof, or emotionally unavailable. These caregivers tend not to be present or attentive to the child. This creates an experience where the child develops self-sufficiency and pulls away from parental support.

In the experiment, while the caregiver was present, the toddlers with an avoidant attachment style engaged with the toys but appeared uninterested or unresponsive to their caregiver. When the caregiver left, the toddler didn’t show significant distress and even ignored the caregiver upon their return.

Anxious-ambivalent attachment

Anxious-ambivalent kids tend to have caregivers who are inconsistent in supporting them. Sometimes the caregivers are there, other times not. Or the caregiver might try to be attentive, but that is entirely unattuned to the child’s emotional needs. When the child is upset, instead of being with the child’s emotions, the parent might tell the child to “cheer up” or insist the child stop crying to appease their own discomfort with the feelings.

This creates a confusing experience for the child who wants love and support and is receiving something different. The world feels unpredictable, so the child clings to the attention they do get.

In the Strange Situation test, anxiously attached children played with the toys but looked back frequently to their caregiver, checking in if they were still present. When the caregiver left the room, the child experienced extreme distress. Even when the caregiver returned, the children would return to the caregiver, and stay by their side, often not engaging with the toys again.

Fearful-avoidant attachment

Fearful-avoidant children tend to grow up in chaotic, or even abusive, households where sometimes their caregiver shows them love, and other times the caregiver creates an atmosphere of danger. This leads to a dynamic where the child both wants parental connection and is terrified of it.

Children with disorganized attachment played with toys and explored the room like others. But when the caregiver left and came back, the child would usually crawl towards them, seeking safety but then freeze. They want the affection of their caregiver but also fear them at the same time.

Childhood patterns turn into adult patterns

Attachment theory postulates that the patterns these four categories of children feel towards their caregivers remain imprinted in their psyches as they become adults and forge bonds with others.

In fact, researchers studied the same children that participated in Ainsworth’s Strange Situation test twenty years after the original study7https://srcd.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1467-8624.00176, and 72% received the same secure vs. insecure attachment classification.

The secure children who felt reassured by their caregivers became secure adults who could create trusting, intimate bonds.

The avoidant children who ignored their caregivers became avoidant adults who avoided intimacy and preferred not to rely on others.

The anxious children who felt devastated by the absence of their caregiver became anxious adults who felt unsafe and uncertain that their partners loved them and would stay with them.

And the fearful children who felt desire and fear towards their caretaker became fearful adults who anxiously wanted more intimacy but felt avoidant once they got it.

As adults, when we form a deep enough bond with another person—whether romantic, sexual, friendship, or otherwise—we start to attach to that person. And when we attach, all of our childhood attachment patterns come roaring out.

Multiple attachment figures

About half of the babies are primarily attached to their mother, half to their father, and some to grandparents or siblings, according to a longitudinal study8https://assessmentpsychologyboard.org/edp/pdf/Attachment_Theory–Schaffer_and_Emerson.pdf conducted by psychologists Rudolph Schaffer and Peggy Emerson in the 1960s.

Schaffer and Emerson also found that infants can experience multiple attachments at once—and having a primary attachment to one caregiver does not preclude the baby from forming attachments to other caregivers.

This adds some useful color to the picture because it indicates that while our primary attachment pattern may stem from our relationship with our primary caregiver, we each may possess the seeds for multiple attachment patterns depending on our relationships with all of our caregivers.

This also indicates that as adults, we may display different attachment patterns with different people, depending on which childhood caregiver imprint they may evoke.

Now that we know the nuts and bolts of attachment theory let’s explore the major characteristics of the three insecure attachment types.

Common Characteristics of Each Insecure Attachment Style

As you read through the insecure attachment types, remember that you are not permanently beholden to your default attachment style. Our attachment styles are our default responses to intimacy we developed as kids—but with enough self-inquiry, healing, and positive experiences, we can all develop a secure attachment style.

Avoidant-dismissive attachment characteristics

Remember that avoidant children (even as one-year-olds) tend not to lean on their caregiver for support. This way of moving through the world comes out in adulthood as well. Here are nine of the hallmark characteristics of dismissive-avoidant adults. See if either you or your partner relates with any of them.

- Highly valuing independence: Dismissive avoidant folks often prioritize self-sufficiency and independence, even to the point of avoiding close relationships to maintain their autonomy.

- Difficulty with emotional intimacy: They may struggle with emotional closeness and vulnerability in relationships, often avoiding or downplaying emotional conversations. When things become too emotionally close, it can feel intense and cause an avoidant person to require space.

- Keeping their inner world private: Dismissive avoidant folks might reveal little about their inner thoughts, feelings, or personal experiences, maintaining a high level of privacy.

- Suppressing feelings: Avoidant adults tend to suppress or dismiss their emotions, particularly those associated with vulnerability, such as fear, sadness, or need for comfort. Often they may intellectualize or rationalize their emotions and minimize the significance of their feelings.

- Avoidance of physical affection: A cuddle party might seem like an overwhelming nightmare to a dismissive avoidant person! They may be uncomfortable with physical intimacy or affection, seeing it as a potential intrusion of their boundaries of self.

- Dismissive attitude towards relationships: Some avoidant people might dismiss and look down upon the importance of close relationships and may claim that they do not need others for emotional support.

- Difficulty seeking support: For avoidant folks, asking for help can be very hard, even if they struggle deeply. Asking for help means leaning on someone else; that emotional dependency feels foreign to them.

- Reluctance to commit to relationships: They may avoid making long-term commitments in relationships, often fearing that it could lead to a loss of independence. This can be observed in both romantic and platonic relationships, as they may want to keep their “options open.”

Note that these characteristics have both plus sides and downsides. There is a huge benefit that comes from a proclivity towards independence and self-sufficiency. And there is also a loss of human connection when we don’t let people get too close to us.

Anxious-preoccupied attachment characteristics

Anxious children cling to their caregivers and resist exploring the world without their support. Here are ten of the hallmark characteristics of anxious-preoccupied adults. See if either you or your partner relates with any of them.

- Fear of abandonment: They may constantly fear that their partners will leave them, leading to a heightened sense of insecurity in their relationships.

- Clinginess: They might be overly dependent on their partners and seek constant reassurance and attention, which can sometimes be perceived as “needy.”

- High emotional sensitivity: They tend to be highly sensitive to their partner’s moods, actions, and any perceived changes in the level of interest or affection.

- Relationship anxiety: They often worry about their partner’s commitment to the relationship and tend to perceive small issues as potential threats to their relationships.

- Need for validation: They frequently seek approval and validation from their partners, and their self-esteem is closely tied to their partners’ reassurance.

- Rollercoaster relationships: Their relationships may be full of highs and lows, with intense love and affection swinging to intense anxiety and fear of loss.

- Overanalyzing: They may overanalyze their relationships, spending a lot of time thinking about their interactions and worrying about the state of the relationship.

- Struggle with boundaries: They may have a hard time setting and maintaining boundaries, often merging their identity with their partner’s.

- Difficulty focusing on self: They may focus so much on their partner and the relationship that they neglect their own needs, interests, and self-care.

- Pedestaling their partner. Anxious-preoccupied individuals might put their partner on a pedestal as someone who they must impress and whose approval they must earn.

One primary strength of anxiously attached folks is their capacity for empathy and attunement to others’ emotions. Individuals with an anxious attachment style tend to be very attuned to the emotional states of others, often showing a deep understanding and sensitivity to their partner’s feelings.

This emotional awareness can make them highly empathetic and caring partners, capable of deep emotional connections when their anxiety is managed.

Disorganized attachment characteristics

Fearful attachment style develops from a childhood environment where the caregiver is both a source of comfort and fear, leading to confusion about whether to seek or avoid them. This can result in several distinctive behaviors and feelings in the relationships of adults with disorganized attachment:

- Push-pull with intimacy: Adults with a disorganized attachment style might crave close intimacy with others, but once they get it, it can feel overwhelming and terrifying, causing them to freeze, lash out, or push the other person away.

- Inconsistent behavior: Their behavior in relationships can be unpredictable and contradictory, swinging between being overly involved and withdrawn.

- Difficulty trusting others: They often struggle to trust their partners due to their past experiences with unreliable or harmful caregivers.

- Difficulty regulating emotions: They may have trouble managing their emotions, leading to periods of intense, overwhelming feelings that can be difficult for both themselves and their partners.

- Unresolved trauma: Many adults with disorganized attachment have experienced trauma, which can resurface in their adult relationships in the form of fear, anxiety, or dissociation.

- Disconnection from self: They may struggle to understand their needs and emotions, often because they had to suppress their feelings as a child in response to an unpredictable or harmful caregiver.

Despite the difficulties associated with a disorganized or fearful-avoidant attachment style, individuals with this style can possess considerable resilience and adaptability. One significant strength is their capacity for self-reflection and introspection. Because of their complex attachment experiences, they often develop a deeper understanding of human emotions and behavior.

When this introspective ability is channeled positively, it can result in a profound level of self-awareness, an important step in personal growth and building healthier relationships.

Strategies and Techniques for Addressing and Healing Insecure Attachments

It’s important to emphasize that there is nothing wrong with having an insecure attachment style. It’s okay to feel avoidant, anxious, or fearful of intimacy. You can still create meaningful connections.

And, if you choose, there is a healing path toward developing a secure attachment style. It’s a journey that involves self-awareness, self-compassion, healthy relationships, and often professional help. When you start with an insecure attachment style and eventually develop a secure attachment style, it’s often called an “earned” secure attachment style.

No matter how much you heal, your old impulses and patterns might still arise, but you can increase your agency over how you relate to them and build your confidence in creating healthy intimate bonds…

Here are some general strategies for each type of insecure attachment:

Dismissive-avoidant strategies:

- Note your patterns: Awareness is always the first step toward making change! As you relate with people, just notice when avoidant patterns emerge.

Action step: Carry a notebook around with you for a day, and jot down every time you notice any of the following impulses, what event preceded it, and any other salient feelings or thoughts:

- The impulse to run from a social situation

- The desire to hide your experience from another

- The impulse to push someone away from you

- The sense that you have to do it all alone

- Understanding and expressing emotions: This involves learning to recognize and express emotions healthily. You might always have an impulse to suppress your emotions or keep them to yourself. But the more you can share them with trusted people, the deeper bonds you can forge.

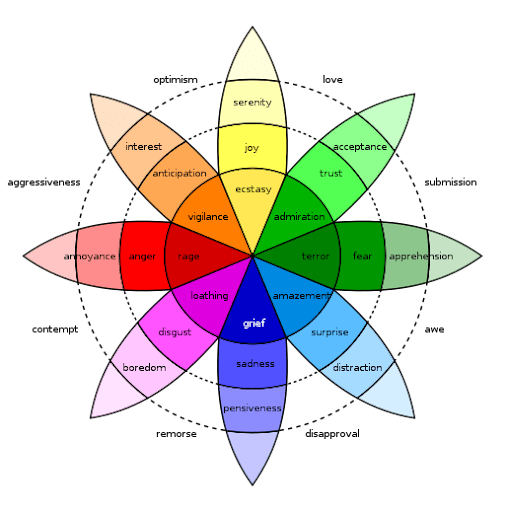

Action step: Journal for five minutes on what emotions you notice in your experience right now using the emotion wheel. Bonus points if you do this several times throughout the week.

Action step: Find someone in your life who feels safe and trustworthy, and share your emotions with them. You don’t have to go 100% vulnerable right away—but reflect on if there was any frustration, anxiety, or sadness you experienced recently, and try sharing it with a trusted friend.

- Share appreciation: It’s notoriously petrifying for avoidant attached folks to open up to others. If you feel up for the challenge, try taking on this fear.

Action step: Pick a person in your life who you genuinely appreciate and who feels safe to you. Next time you see them, share an appreciation with them. It could be a quality of theirs you admire or simply the fact that you are friends with them.

- Ask for support: Dismissive-avoidant individuals tend to be diehard independents—even to their detriment. To start to untangle this pattern, you can try to go out of your way to ask for support. This might feel like the most alien thing ever, but see if you can give it a shot.

Action tip: Ask someone in your life for support sometime this week. It could help with a project, help to talk through an issue in your life, or maybe just help fill a social need by hanging out.

Anxious-preoccupied attachment strategies:

- Note your patterns: It’s always good to start with awareness! As you relate with people, notice any anxious patterns that emerge.

Action step: Carry a notebook around with you for a day, and jot down every time you notice any of the following impulses, what event preceded it, and any other salient feelings or thoughts:

- The feeling that another person’s approval will make you feel good about yourself, and their disapproval bad about yourself

- The impulse to sacrifice your own boundaries (time boundaries, personal preferences, etc.) to be liked by another person

- The fear that someone in your life is on the verge of “breaking up” with you

- Putting another person on a pedestal and feeling you have to impress them.

- Self-Soothing techniques: This involves learning how to comfort oneself during times of anxiety or distress.

Action step: The next time you feel anxious, scan your five senses for something that gives you pleasure—it could be a tree branch swaying in the wind, the feeling of cool air on your cheeks, the sound of children playing down the block, or anything else. Put your attention on this resourcing stimulus for several minutes, and let it soothe your nervous system.

- Setting boundaries: Understanding your needs and setting boundaries can empower you, create a sense of certainty in yourself, and prevent overdependence on others.

Action step: Speak up about one boundary this week. Maybe your partner asks for a favor that you don’t have the capacity to help with, or your boss asks you to complete a task faster than you’re comfortable doing.

- Solo date! Taking quality time for yourself can help you reinforce your sense of self, your personal worth, and your independence.

Action step: Pick one evening this week, and spend at least three hours following your desire. That might mean taking a bubble bath, going on a hike, or shopping. Whatever sounds enjoyable for you and you alone.

Disorganized attachment strategies:

- Note your patterns: Again, begin with awareness. Look for any consistent patterns in your relationships.

Action step: Carry a notebook around with you for a day, and jot down every time you notice any of the following impulses, what event preceded it, and any other salient feelings or thoughts:

- Sending mixed signals to someone

- Feeling afraid of getting closer

- The need to control a person or social situation

- Doubting others’ intentions in innocuous situations

- Feeling disproportionately intense emotions in social settings

- Mindfulness and grounding techniques: Folks with disorganized attachment can experience intense emotional ups and downs. So it’s critical to develop techniques to help manage intense emotions and become more present during times of distress.

Action step: Once a day for the next week, spend two minutes trying out the following meditation:

- Close your eyes

- Notice your feet on the ground

- Imagine that the Earth is supporting you

- Continue to shift your awareness from your feet to the feeling of support from the Earth

Action step: The next time you feel emotionally overwhelmed, try the 5-4-3-2-1 technique coping technique for anxiety9https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/behavioral-health-partners/bhp-blog/april-2018/5-4-3-2-1-coping-technique-for-anxiety.aspx.

- Identify: five things you can see (couch, TV, tree, etc.)

- four things you can touch (hair, pillow, sweatshirt, etc.)

- three things you can hear (traffic sounds, buzzing, etc.)

- two things you can smell (a bar of soap, food nearby, etc.)

- and one thing you can taste (what’s your mouth taste like?)

Finding External Support

Finding security in relationships is often a transformative journey for individuals with insecure attachment styles.

Connecting with secure partners

While self-practices are critical to developing a secure attachment style, often, this journey of healing will involve healthy, stable relationships with securely attached individuals.

A secure partner can provide a consistent sense of safety and reliability, demonstrating what a balanced, mutually respectful relationship looks like through actions and words. They can help to model healthy communication, appropriate boundaries, and consistent emotional availability. They can also offer the understanding and patience required to navigate the complexities of insecure attachment instead of getting triggered into their own insecure attachment spiral.

Over time, these experiences can challenge and reshape insecure attachment patterns, guiding the journey toward greater security and relational satisfaction.

With enough exposure to your own adult cloth monkey (so to speak), your nervous system can start to trust that that person is there for you, is trustable, and can help you soothe and restore yourself.

Seeking help and resources

For many, seeking a therapist or other professional support can dramatically catalyze their healing path to security.

One excellent option is Psychology Today’s directory of therapists specializing in attachment.

Another option is to work with an intimacy coach from the Somatica Institute, where the approach is more relational. Within a clear container with tight boundaries, the coach and client will create an intimate bond, which will bring forth the client’s attachment pattern, and the trained coach will then actively help the client build trust and heal whatever-related wounds arise.

Frequently Asked Questions About Insecure Attachment

The three insecure attachment styles are: avoidant-dismissive (called “anxious-avoidant” when referring to children), where you might push your partner away; anxious-preoccupied (called “anxious-ambivalent” when referring to children), where you might feel anxious over your partner’s interest in you; and fearful-avoidant (called “disorganized” when referring to children), where you might crave connection but also feel frozen when you get it.

Insecure attachment is caused by genetic predisposition and a baby’s relationship to their caregiver. Three common relationship dynamics that might cause an insecure attachment style are: the caregiver doesn’t give the child enough empathy and affection; the caregiver gives the child inconsistent attention; the caregiver abuses the child physically or emotionally.

An example of avoidant-dismissive attachment might be if your partner asks you for a deeper commitment, you feel pressured, and you push them away. An example of anxious-preoccupied attachment might be if you overanalyze all of your interactions with your partner because you aren’t sure if you did something that might cause them to stop liking you and then withhold their affection. And an example of disorganized attachment might be if you feel like you need more intimacy from your partner, but when they give it to you, you panic.

One common characteristic across all three types of insecure attachment is anxiety linked to intimacy. Either there is an anxiety that there is never enough intimacy (and security), or there is an anxiety that the intimacy has become overwhelming, or both.

You can tell if your attachment style is insecure if any of your past close relationships are marked by either a feeling of constant stress that your partner might leave at any time or the sense that any time you get deep enough into a relationship, you immediately stop liking the other person, or if you’ve avoided intimate relationships altogether.

The three types of insecure attachment in infants are anxious-avoidant, anxious-ambivalent, and fearful-avoidant. In adulthood, these patterns become avoidant-dismissive, anxious-preoccupied, and disorganized, respectively.

Disorganized attachment is the rarest style, accounting for 1-5% of the population. About 23% of adults are avoidant-dismissive, 15% anxious-preoccupied, and roughly 60% are secure.

You can have both avoidant and anxious attachments. If you quickly toggle between these two attachment styles within the same relationship, you might have a disorganized attachment style. But it’s also common to experience avoidant tendencies in some relationships and anxious tendencies in others. This is because, as children, many of us had multiple caretakers (parents, siblings, grandparents), and each imprinted the potential for a different attachment pattern onto us.

The three best ways to create a secure attachment style are to develop tools to counteract your insecure impulses, to work with a therapist to heal your childhood wounds and fears, and to foster deep relationships with individuals with a secure attachment style.

Moving Forward for Insecurely Attachment Folks

Nearly half of the adults have an insecure attachment style, which is largely attributed to how their caretakers related to them as children.

Remember that insecure attachment is not a life sentence but a pattern that can be understood, addressed, and, over time, healed. Through the personal techniques we went over, working with professional support, and finding secure relationships, you can earn your own secure attachment style.

In the words of relationship psychologist and author Dr. Sue Johnson10https://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/22726.Sue_Johnson, “In insecure relationships, we disguise our vulnerabilities so our partner never really sees us.” But in facing our insecurities and embracing the potential for change, we can allow our true selves to be seen and, more importantly, securely loved.

If you’d like to clarify your attachment style, this free quiz is a great place to learn more about yourself.

Article sources

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/24440045_The_first_10000_Adult_Attachment_Interviews_Distributions_of_adult_attachment_representations_in_clinical_and_non-clinical_groups

- http://www.psychology.sunysb.edu/attachment/online/inge_origins%20DP1992.pdf

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3051370/

- https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Bartholomew-and-Horowitzs-1991-model-of-adult-attachment_fig1_275367267

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8474999/#:~:text=shaped%20throughout%20development.-,Genetic%20research%20indicates%20that%20up%20to%2045%25%20of%20the%20variability,be%20explained%20by%20genetic%20causes.

- https://www.psychalive.org/how-your-attachment-style-affects-your-parenting/

- https://srcd.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1467-8624.00176

- https://assessmentpsychologyboard.org/edp/pdf/Attachment_Theory–Schaffer_and_Emerson.pdf

- https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/behavioral-health-partners/bhp-blog/april-2018/5-4-3-2-1-coping-technique-for-anxiety.aspx

- https://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/22726.Sue_Johnson

How to Deal with Difficult People at Work

Do you have a difficult boss? Colleague? Client? Learn how to transform your difficult relationship.

I’ll show you my science-based approach to building a strong, productive relationship with even the most difficult people.