Shakespeare’s “Midsummer Night’s Dream” recounts the tale of two couples who, due to some fairy mischief, spend an enchanted night falling in and out of love before all is righted in the end.

At the height of the confusion, Hermia is flabbergasted when her lover, in trying to prove he no longer cares for her, says

”What, should I hurt her, strike her, kill her dead?

Although I hate her, I’ll not harm her so.”

To which the devastated Hermia responds, “What, can you do me greater harm than hate?”

Through the ages, music, art, and performance have grappled with how to portray hate, its devastating impact, and the relief of giving it up.

We’re a society that loves to hate things. 67% of survey respondents hate admitting their wrong1https://markets.businessinsider.com/news/stocks/it-wasn-t-my-fault-new-study-looks-at-why-people-hate-admitting-mistakes-1028435641, 5% of US workers admit they hate their job2https://news.gallup.com/opinion/chairman/212045/world-broken-workplace.aspx?g_source=position1&g_medium=related&g_campaign=tiles, and tragically, one person in every 1,0003https://bjs.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh236/files/media/document/hcv0519_1.pdf in the US was a victim of a nonfatal hate crime in 2019.

With the same word describing such a huge range of experiences, you might wonder what hate actually is.

What is Hate?

Hate is an intense aversion or hostility towards someone or something. It involves a strong negative emotional response and often includes a desire to harm, devalue, or exclude the target of hatred.

From a psychological standpoint, hate is a secondary emotion, a learned response from personal experiences, social conditioning, and cognitive processes.

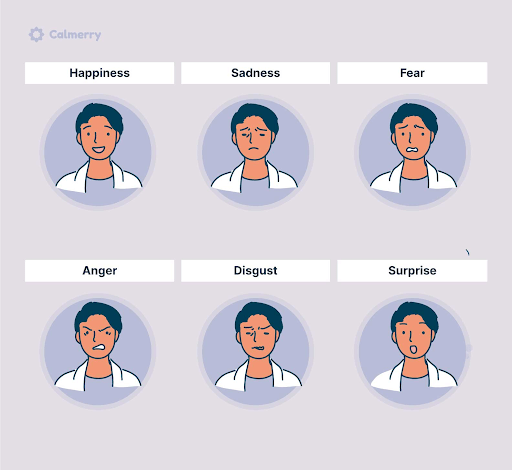

Primary emotions4https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00781/full, like anger, fear, or disgust, are fundamental to evolution and adaptation. They are universal, shared across cultures, and present from infancy (more on that later). These basic emotions have distinct physiological and facial expression patterns.

Source: Calmerry

Let’s consider hate in the context of a few other emotions:

- Anger is a temporary emotional response to a perceived provocation or threat. It involves feelings of frustration, irritation, or resentment. A specific incident can prompt it and may dissipate once the situation is resolved, while hate is deep-seated and often longer lasting.

- Dislike is a milder negative emotion towards someone or something. It’s more of a lack of positive feelings without the intense hostility associated with hate. Dislike can be based on personal preferences, differences in opinions, or minor irritations.

- Love is often viewed as the opposite of hate. However, they’re actually two sides of the same coin. Love is an intense positive emotion and affinity for something or someone, while hate involves intense negative emotions and a strong aversion or hostility towards someone or something.

- Apathy, or indifference, where there is a lack of emotional connection or concern, is better viewed as the opposite of both love and hate.

Unlike these other emotions, hate is a strong negative attachment that isn’t focused on any one specific target. It’s a destructive force that, at its worst, can perpetuate discrimination, violence, division, and oppression among individuals and communities.

Watch our video below to learn why fake friends are ruining you and how to end a friendship:

The 4 Types of Hate

Understanding the different ways that hate can manifest in day-to-day interactions is crucial to identifying and addressing issues before they escalate. It may not change the world, but one vocal advocate in a room, especially someone in a position of privilege, can change the course of an interaction, a conversation, and perhaps a life.

Microaggressions

Microaggressions are subtle, often unintentional, everyday actions or comments that marginalize and demean individuals based on their identity or background. One study indicated that in a twelve-month period, up to one in four Black and Latinx students5https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2017-54288-010 were victims of racial microaggressions.

Check out this video where a group of black men discuss microaggressions in their everyday life.

Often, microaggressions are more obvious to the recipient than the speaker. In some cases, the comment wasn’t intended to be hurtful and needs to be pointed out for the speaker to realize the impact of their statement.

What can you say if you hear someone making a comment that could be a microaggression? Here’s an idea:

“I know it may not have been intentional, but remember during the meeting when [specific incident]? It made me uncomfortable because [share how it affected you or others]. That comment felt like a microaggression.”

Hate Speech

Hate speech is when someone says or writes things that spread hate, discrimination, or prejudice against people based on things like race, religion, gender, or other protected characteristics. It is generally more intentional than microaggressions but more challenging to address.

When you hear hate speech, it may be tempting to either ignore it to avoid confrontation or lash out and call the person out for their offensive comment. Unfortunately, the first reaction lets the speaker believe what they said is OK. In contrast, the second is likely to make the other person defensive and leave, justifying their comment by deciding you are just too sensitive.

While it won’t be comfortable, addressing racism and other hate speech—especially in work environments—is important to ensure all employees feel valued and supported. Here’s an example of a manager doing that:

- Manager: We need to discuss the comment you made during today’s meeting.

- Employee: Oh, calm down. It was just a joke. Don’t be so sensitive.

- Manager: This isn’t about sensitivity; it’s about respect. Your so-called joke perpetuates harmful stereotypes and contributes to a toxic environment.

- Employee: Whatever, I didn’t mean anything by it.

- Manager: That’s not an excuse. Your words have consequences, and in this office, we don’t permit comments that belittle and stereotype people. I’d like to set up a meeting so you can apologize to [the other person], and they can explain why that comment was harmful.

Hate Crimes

Hate crimes are criminal acts committed against individuals or groups based on their perceived race, ethnicity, religion, nationality, sexual orientation, gender identity, or other protected characteristics.

They can take various forms, including physical assault, vandalism, threats, harassment, or even murder. They not only harm the immediate victims but also have a broader impact on the targeted community, spreading fear, intimidation, and division.

Regardless of differences in opinion or ideology, there is no place for hate crimes. Not at home, at work, or in society.

If you think you are seeing hate crimes, document the experience. Research is clear6https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/video/your-memories-are-not-as-true-as-you-think/ that memory isn’t very reliable because memories change each time we recall them. As necessary, inform work management or law enforcement of situations that could escalate to hate crimes.

Action Tip: Learn de-escalation techniques to support yourself or others in anxious or hostile situations.

Cyberbullying

The ubiquitous nature of technology in our society has led to staggering statistics about cyberbullying. Research shows7https://techjury.net/blog/cyberbullying-statistics/ that 46% of US teens aged 13 to 17 have been bullied online, and 41% of US adults have experienced cyberbullying.

Hate plays a significant role in cyberbullying as it fuels the intent to harm, intimidate, or humiliate others online. Perpetrators often use hateful language, slurs, or derogatory remarks to target their victims based on their perceived differences or vulnerabilities.

Meanwhile, the anonymity and distance provided by the digital environment can amplify the expression of hate, enabling cyberbullies to freely spread messages of discrimination, prejudice, and bigotry with potentially severe psychological and emotional consequences for their victims with minimal consequences for themselves.

Action Tip: Take a moment to evaluate your social media accounts. Consider the tone of your posts, the content you share, and the accounts you follow. Make a conscious effort to ensure your online presence aligns with promoting tolerance, respect, and inclusivity

Why Do People Hate?

It’s fascinating to think that, as humans, we aren’t born with the ability to hate. Young children can exhibit negative emotions like anger8https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5681963/, frustration, or dislike towards certain people or situations. It’s not until they are older9https://ilabs.uw.edu/sites/default/files/17Skinner_Meltzoff_Roots%20of%20Child%20Prejudice.pdf and can understand and articulate complex feelings that they begin to hate.

Social And Cultural Factors

Hate is often influenced by social factors that shape our beliefs and attitudes. Our upbringing, cultural background, and our society can play a significant role in fostering hate.

Humans desire structure and certainty in their social lives. To establish that, people naturally divide into in-groups (social circles where everyone feels like they belong with one another) and out-groups (people who exist outside of social circles and are typically not welcomed into them).

When people declare their dislike for others, it helps people understand the boundaries10https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.320.8566&rep=rep1&type=pdf between social circles. This is a powerful motivator for people to form bonds because it satisfies their need to feel connected to others.

Fundamentally, hate stems from an “us vs. them” mentality, a psychological inclination to identify with our own group and view others as different or threatening.

For example, studies show11https://earlylearningnation.com/2021/02/what-do-young-children-know-about-race-you-might-be-surprised/ infants can differentiate between black and white faces, and by nine years old, children understand the social implications of race, including stereotypes.

Unchecked, this mentality leads to implicit bias12https://diversity.nih.gov/sociocultural-factors/implicit-bias within a society or culture—which has prompted conflicts and divisions based on religion, ethnicity, and nationality throughout history.

Think of religious conflicts like the Crusades and the Spanish Inquisition, racial and ethnic conflicts such as slavery, colonialism, and apartheid, or political ideologies that fueled hatred, such as fascism and totalitarianism.

Group dynamics and the desire to fit in can lead people to adopt and amplify hateful views to gain acceptance or maintain their identity within a particular social circle. Additionally, competition for resources, power, or status can fuel animosity.

For example, when someone new enters a group, particularly if they are in a position of influence, many people immediately begin gossiping negative things about the person because they fear how that individual will change their group dynamics. Sharing hatred toward the new person is a way for the existing group to strengthen their bonds in defense against the outsider.

Many people join hate groups because it fills their need for friendship and belonging. You don’t need to do or be anything special; all you have to do is be negative toward other people. It feels easy. Likewise, some people find it easier to make connections by putting others down and seeing who agrees than to prove to people that they are interesting and valuable companions.

Check out this TED talk from a childhood bully turned activist about addressing a culture of hate.

What we can do about the culture of hate | Sally Kohn

Addressing hate at a societal and cultural level requires challenging societal biases, promoting inclusivity, and fostering understanding between diverse groups. It also requires recognizing our shared humanity, fostering empathy, and promoting dialogue and cooperation among diverse groups. We’ll talk more about how to do that shortly!

Action Tip: Spend 10 minutes on Harvard’s Project Implicit website to test areas where you have implicit bias.

Psychological and Emotional Factors

The psychological roots of hate are complex and multifaceted. They often come from negative personal experiences where the person’s identity or beliefs are attacked. Such experiences can breed deep anger, resentment, and fear.

In other situations, people want a scapegoat. When you struggle with problems at work, low self-esteem, conflicts in your relationships, etc., it feels much better to funnel your negative energy into blaming someone else than to confront your role in your problems.

Hatred also surfaces when people are highly insecure. Often, they’ll compare themselves to other people. When they conclude that the other person may be better than them or possess undesirable traits that they don’t want to acknowledge having themselves, people may speak out against that person to project their anxiety onto them.

Sometimes, our negative feelings are an unconscious reaction to nonverbal cues we pick up on. Check out Why We Love to Hate Certain Celebrities for some great examples.

Action Tip: Challenge your assumptions that can lead to bias and hate. For example, when someone cuts you off in traffic, your first instinct may be to think they—and everyone else who drives that same car—are reckless, thoughtless individuals whose goal in life is to anger you. (Been there). However, your second thought could be, “I wonder if they were running late and didn’t see me merging into the lane.”

Is it true?

Maybe, maybe not. But it’s no more or less accurate than the first story you told yourself.

Impacts Of Hate And Conflict

Now that we’ve looked at some ways hate can be present in our society, let’s look at its effect on various individuals and groups.

Self-Hatred

Self-hate is an intense dislike, loathing, or hostility toward oneself. It’s particularly insidious because it can manifest in socially acceptable ways and can be hard to identify from the outside.

It can present as:

- Perfectionism

- People pleasing

- Self-deprecating humor or other negative comments

- Body image issues that can lead to mental and physical illness

Unfortunately, self-hate can lead to low self-worth, increased stress, anxiety, depression, or other mental health challenges and hinder personal growth and relationships.

Addressing self-hate requires you to recognize and acknowledge negative self-talk, self-destructive patterns, or harmful beliefs. With professional help from a counselor or therapist and a support network, it’s possible to address and rewire your brain’s neural pathways by challenging negative thoughts or unrealistic standards and practicing self-care.

Interpersonal Conflict

What would Back to the Future be without the hate-fueled rivalry between Biff and the McFlys?

While we love to watch, hate play out in movies or books, real-life interpersonal conflict can range from mildly annoying to life-shattering.

Unchecked hate can appear as bullying, marginalization, or discrimination. In relationships, it can break down trust and communication and, at worst, lead to verbal or physical abuse. When directed at a particular group, hate can lead to discrimination and prejudice and escalate to violence.

As an individual, there are some things you can do to help minimize interpersonal conflict:

- Practice self-awareness

- Cultivate empathy and understanding

- Choose constructive communication

- Seek common ground

- Practice active listening

In Communities And Societies

During World War II, hate and racial prejudice fueled by wartime hysteria and fear led to the establishment of Japanese internment camps. Thousands of Japanese Americans were forcibly relocated and detained based solely on their ethnicity, resulting in the violation of their civil rights and the perpetuation of discrimination.

Unfortunately, it’s not hard to find similar stories on large and small scales worldwide today. But when we as individuals allow acts of hate to go on without comment, society as a whole loses some of our unity, dignity, diversity, and safety.

It’s essential to foster a society that values diversity, promotes empathy, and actively challenges hate and discrimination to avoid repeating such injustices of the past.

How? You can start by educating yourself about other cultures, religions, and backgrounds. You might start by learning the history of dance from another culture, attending a religious service besides your own, or inviting someone from a different background over for dinner.

I went to a festival recently and stopped at a booth with Polynesian carved necklaces. I started leafing through a binder with the lore and significance of the symbol. Learning the stories behind these necklaces made them even more beautiful to me and left far less room to dismiss them as unimportant.

So, ready to set some goals on how to combat hate in your life and community?

How To Set Better Goals Using Science

Do you set the same goals over and over again? If you’re not achieving your goals – it’s not your fault!

Let me show you the science-based goal-setting framework to help you achieve your biggest goals.

The Surprising Advantages Of Hate

While counterintuitive, there are actually some benefits to expressing hate for a third party. Research shows that mutual dislike evokes a stronger response than mutual like.

In one study13https://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/10/magazine/10Section2b.t-7.html, people were shown a video of two people conversing in which the man politely hit on the woman. After being asked if they liked or disliked the man, they were told they would meet people who shared their opinion of them and asked how likely they were to get along with the person they met.

People who had a negative opinion of the man were far more likely to say they would get along well with someone who shared their negative opinion than those who had a positive opinion.

This concept can explain why highly ideological groups—political or social—often find great success in slamming people or ideas from the opposing side.

Research14https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0265407519853047 also shows that to form lasting, intimate bonds with people; you have to be vulnerable with them. That is, you have to share your authentic, unfiltered feelings. Instead of being negative toward another person because of the internal struggles described above, you may share that you hate someone for a valid, personal reason, such as they hurt you or hurt someone and/or something you care about.

This instance is a moment of vulnerability because you share a difficult experience that can lead others to hate the other person on your behalf and bond with you.

Now, that said, while there are some bonding benefits to spewing negativity about other people, don’t try to use this tactic to make friends because its risks far outweigh any good that comes from it. Be aware of these potential consequences of speaking poorly about others:

Expressing negative opinions can come at a serious cost to your reputation if the people around you don’t agree. Researchers have discovered that when we hear someone talking about other people, we impose the content of what’s said onto the speaker. It’s a phenomenon called spontaneous trait transference15https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9569648/#:~:text=Spontaneous%20trait%20transference%20occurs%20when,such%20associations%20persist%20over%20time..

To demonstrate, imagine this conversation between two people after meeting another guest at a dinner party.

Charlotte: “What did you think of Mr. Collins, Lizzy?”

Elizabeth: “Ugh, he was so pompous and self-righteous. I couldn’t stand the way he kept looking over at us.”

This can go one of two ways: If Charlotte also thought Mr. Collins was pompous, they would bond over their shared dislike. But, if she thought he was interesting or, at the very least, deserving of a decent review, Charlotte would hear Elizabeth’s opinion and think that Elizabeth is pompous and self-righteous because Charlotte’s brain would unconsciously project those statements onto her friend.

Given these risks, unless your hatred is founded in a socially acceptable ideological belief, comes from a personal experience of being hurt, or could be otherwise justified by most people, it is best to keep it to yourself.

Reactions to Hate

Natural reactions to witnessing or experiencing hate can vary depending on the individual and the circumstances, but they generally fall into “fight, flight, or freeze” categories. Some common reactions may include:

- Anger and Frustration: Seeing or experiencing hate can evoke anger and frustration stemming from a sense of injustice and the violation of fundamental human rights.

- Emotional Distress: Witnessing or being subjected to hate can lead to emotional distress, such as sadness, fear, anxiety, or feelings of powerlessness. It can profoundly impact one’s mental and emotional well-being.

- Empathy and Solidarity: Some individuals may respond with empathy and solidarity, feeling a sense of connection and support towards the targets of hate and seeking ways to stand up against it.

- Motivation for Action: Hate can serve as a catalyst for individuals to take action, whether through advocacy, activism, or promoting positive change in their communities, aiming to combat hate and promote tolerance and inclusivity.

- A Desire for Understanding: Some individuals may feel a strong urge to understand the roots of hate and its underlying causes, seeking knowledge and awareness as a means to address and prevent it.

Responding to Hate

We’ve already discussed many ways to respond to demonstrations of hate on individual and societal levels. Education, promoting cultural understanding, encouraging open dialogue, advocating for inclusive policies, and actively standing against prejudice and bigotry are the groundwork for promoting inclusivity. Here are a few more suggestions.

Overcoming Expressions of Hate

Storytelling for Empathy

Have you been in the room when someone makes a comment that generalizes a group of people? Share your own positive experiences with members of that group. Doing so will challenge stereotypes and promote empathy.

Engage in Constructive Dialogue

A lot of understanding comes from being willing to listen. Engage in respectful and open dialogue with those who hold different opinions. Seek common ground, listen actively, and strive to find areas of understanding and compromise.

Promote Inclusivity and Diversity

Whether you’re a CEO or a cubicle worker, you can encourage diverse voices to be heard, celebrate cultural differences, and advocate for equal opportunities for all.

Making Hate a Thing of The Past

So, after all this discussion, what have we learned about hate?

- Hate is an intense aversion or hostility towards someone or something rooted in personal experiences, social conditioning, and cognitive processes.

- Reasons for developing strong feelings of dislike or hatred include misunderstanding, negative experiences, societal influence, fear of the unfamiliar, and personal insecurities or biases.

- Hate is influenced by social and cultural factors, such as upbringing, cultural background, and the desire for belonging. It often stems from an “us vs. them” mentality, leading to discrimination, violence, and division.

- Psychologically, hate can be fueled by negative personal experiences, the need for a scapegoat, insecurity, and unconscious reactions to non-verbal cues.

- Different types of hate include microaggressions, hate speech, hate crimes, and cyberbullying. They significantly impact individuals, perpetuating self-hate, interpersonal conflicts, and societal divisions.

- Addressing hate requires challenging biases, promoting inclusivity, fostering empathy, and encouraging dialogue and cooperation among diverse groups. It starts with self-awareness, choosing constructive communication, seeking common ground, and practicing active listening.

Ready for something a little more upbeat? Check out How to Be Happy: 15 Science-Backed Ways To Be Happier Today.

Article sources

- https://markets.businessinsider.com/news/stocks/it-wasn-t-my-fault-new-study-looks-at-why-people-hate-admitting-mistakes-1028435641

- https://news.gallup.com/opinion/chairman/212045/world-broken-workplace.aspx?g_source=position1&g_medium=related&g_campaign=tiles

- https://bjs.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh236/files/media/document/hcv0519_1.pdf

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00781/full

- https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2017-54288-010

- https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/video/your-memories-are-not-as-true-as-you-think/

- https://techjury.net/blog/cyberbullying-statistics/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5681963/

- https://ilabs.uw.edu/sites/default/files/17Skinner_Meltzoff_Roots%20of%20Child%20Prejudice.pdf

- https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.320.8566&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- https://earlylearningnation.com/2021/02/what-do-young-children-know-about-race-you-might-be-surprised/

- https://diversity.nih.gov/sociocultural-factors/implicit-bias

- https://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/10/magazine/10Section2b.t-7.html

- https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0265407519853047

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9569648/#:~:text=Spontaneous%20trait%20transference%20occurs%20when,such%20associations%20persist%20over%20time.

68 thoughts on “Why People Hate: The Science Behind Why We Love to Hate”

Comments are closed.

How to Deal with Difficult People at Work

Do you have a difficult boss? Colleague? Client? Learn how to transform your difficult relationship.

I’ll show you my science-based approach to building a strong, productive relationship with even the most difficult people.

It’s always easier to find a solution when you look from the outside at other people’s relationships, parents don’t live forever and can not always protect you, but to me divorce is the best ever legal legislation invented, it saves lives, hatred kills people it’s not always physical sometimes brains can be damaged beyond repair.

It’s always easier to find a solution when you look from the outside at other people’s relationships, parents don’t live forever and can not always protect you, but to me divorce is the best ever legal legislation invented, it saves lives, hatred kills people it’s not always physical sometimes brains can be damaged beyond repair.

It’s always easier to find a solution when you look from the outside at other people’s relationships, parents don’t live forever and can not always protect you, but to me divorce is the best ever legal legislation invented, it saves lives, hatred kills people it’s not always physical sometimes brains can be damaged beyond repair.

It’s always easier to find a solution when you look from the outside at other people’s relationships, parents don’t live forever and can not always protect you, but to me divorce is the best ever legal legislation invented, it saves lives, hatred kills people it’s not always physical sometimes brains can be damaged beyond repair.

It be OH SO NICE to have this info in a pocket size booklet. Sealed cover for protection a must.

It’s going to get messed up quickly from pulling out & in a lot, mainly as a reference for others to “GET IT”.

THANKS SO MUCH for this article.

It be OH SO NICE to have this info in a pocket size booklet. Sealed cover for protection a must.

It’s going to get messed up quickly from pulling out & in a lot, mainly as a reference for others to “GET IT”.

THANKS SO MUCH for this article.

It be OH SO NICE to have this info in a pocket size booklet. Sealed cover for protection a must.

It’s going to get messed up quickly from pulling out & in a lot, mainly as a reference for others to “GET IT”.

THANKS SO MUCH for this article.

It be OH SO NICE to have this info in a pocket size booklet. Sealed cover for protection a must.

It’s going to get messed up quickly from pulling out & in a lot, mainly as a reference for others to “GET IT”.

THANKS SO MUCH for this article.

Thank you for this insightful look inside our reasons for hate. As I dwelled more on what you wrote, I found that it is very true. What you wrote in this article is what many of us know in the back of our heads but we never try to address it. When this truth was layed out in front of me, I felt a clearer understanding of my emotions thank you for that.

Thank you for this insightful look inside our reasons for hate. As I dwelled more on what you wrote, I found that it is very true. What you wrote in this article is what many of us know in the back of our heads but we never try to address it. When this truth was layed out in front of me, I felt a clearer understanding of my emotions thank you for that.

Thank you for this insightful look inside our reasons for hate. As I dwelled more on what you wrote, I found that it is very true. What you wrote in this article is what many of us know in the back of our heads but we never try to address it. When this truth was layed out in front of me, I felt a clearer understanding of my emotions thank you for that.

Thank you for this insightful look inside our reasons for hate. As I dwelled more on what you wrote, I found that it is very true. What you wrote in this article is what many of us know in the back of our heads but we never try to address it. When this truth was layed out in front of me, I felt a clearer understanding of my emotions thank you for that.

Exponentially insightful. Thank you for delivering dialogue critical to neutralizing hate.

Exponentially insightful. Thank you for delivering dialogue critical to neutralizing hate.

Exponentially insightful. Thank you for delivering dialogue critical to neutralizing hate.

Exponentially insightful. Thank you for delivering dialogue critical to neutralizing hate.

In my entire working career and life, there’s only One person I truly hated and still do. It’s not because of the reasons stated here, but because he was a snake in the grass, distrusted by everyone who knew him. He was my last boss and no one stood up to him until I met him. When he crossed me several times, I blew the whistle and that’s when his history came out and the company demoted him. Again he was hated not because of all the reasons mentioned in the article; it was because he operated with impunity until someone had the balls to stand up to him. He’s still hated to this day.

Thats awesome because most people keep their tails between their legs for one reason or another. Me, no I live by this quote: IF YOU DON’T STAND FOR SOMETHING YOU WILL FALL FOR ANYTHING! good job for taking a stand….

In my entire working career and life, there’s only One person I truly hated and still do. It’s not because of the reasons stated here, but because he was a snake in the grass, distrusted by everyone who knew him. He was my last boss and no one stood up to him until I met him. When he crossed me several times, I blew the whistle and that’s when his history came out and the company demoted him. Again he was hated not because of all the reasons mentioned in the article; it was because he operated with impunity until someone had the balls to stand up to him. He’s still hated to this day.

Thats awesome because most people keep their tails between their legs for one reason or another. Me, no I live by this quote: IF YOU DON’T STAND FOR SOMETHING YOU WILL FALL FOR ANYTHING! good job for taking a stand….

In my entire working career and life, there’s only One person I truly hated and still do. It’s not because of the reasons stated here, but because he was a snake in the grass, distrusted by everyone who knew him. He was my last boss and no one stood up to him until I met him. When he crossed me several times, I blew the whistle and that’s when his history came out and the company demoted him. Again he was hated not because of all the reasons mentioned in the article; it was because he operated with impunity until someone had the balls to stand up to him. He’s still hated to this day.

Thats awesome because most people keep their tails between their legs for one reason or another. Me, no I live by this quote: IF YOU DON’T STAND FOR SOMETHING YOU WILL FALL FOR ANYTHING! good job for taking a stand….

In my entire working career and life, there’s only One person I truly hated and still do. It’s not because of the reasons stated here, but because he was a snake in the grass, distrusted by everyone who knew him. He was my last boss and no one stood up to him until I met him. When he crossed me several times, I blew the whistle and that’s when his history came out and the company demoted him. Again he was hated not because of all the reasons mentioned in the article; it was because he operated with impunity until someone had the balls to stand up to him. He’s still hated to this day.

Thats awesome because most people keep their tails between their legs for one reason or another. Me, no I live by this quote: IF YOU DON’T STAND FOR SOMETHING YOU WILL FALL FOR ANYTHING! good job for taking a stand….

This article stirred up so many emotions inside me . It gave some words to my feelings and why I have those feelings.

This article stirred up so many emotions inside me . It gave some words to my feelings and why I have those feelings.

This article stirred up so many emotions inside me . It gave some words to my feelings and why I have those feelings.

This article stirred up so many emotions inside me . It gave some words to my feelings and why I have those feelings.

I absolutely hate science it might be my teacher but it’s also the fact that we do like 5 min experiment that is anti-climatic and as stupid as putting salt in water and watching it dissolve (literally we did that) and we spent the rest of the time filling out forms and taking notes on everything! I hate science. Plus it’s not like we use science in real life.

Dear Paige,

I am not sure what grade you are in, but I can understand that sometimes information is not presented in the most captivating way. It is especially hard to like something when we do not understand why we are learning something, or why it’s important, or why we should care.

We also do not have to like every subject out there. Science is a branch of many subjects including Biology, Ecology, Chemistry, Physics, Zoology, Botany, Meteorology, Astronomy, and Social Sciences, to name a few. Individuals can contribute to society in their own field, ultimately working together.

Science is everywhere in real life- from the fuel for vehicles, the weather, medicine, electricity, sport, the internet, and even something simple like salt and water. When we add salt to water it increases the boiling point and decreases the freezing point. This means if you add salt to a pot of water it will take longer to boil, and if you live in a cold climate, adding salt means the water won’t freeze as quickly. You may have heard the expression “cooking is a science!”

Everything from your toothpaste, plastic, the fabrics in your clothes, is a product of science combined with other fields. Mixing baking soda and vinegar creates a chemical reaction that we use for cleaning surfaces and laundry. Even the act of breathing itself is a function of biology and science.

You may continue to “hate science” but hopefully this opens your mind to the way you benefit from or use science in your life every day.

The most important thing you can do is keep an open mind, ask questions like “How do we use science in real life” and when you come across statements that say “never” or “always” consider what exceptions there may be.

Check out Bill Nye the Science Guy if you want to see how nerding out about science can be fun, and help us understand real life!

dear paige,

i think you are ignorant, please consider what you are saying and dont group all of science into a single experience with a sucky experience

*into a hate towards that single entity derived from a sucky experience

I absolutely hate science it might be my teacher but it’s also the fact that we do like 5 min experiment that is anti-climatic and as stupid as putting salt in water and watching it dissolve (literally we did that) and we spent the rest of the time filling out forms and taking notes on everything! I hate science. Plus it’s not like we use science in real life.

Dear Paige,

I am not sure what grade you are in, but I can understand that sometimes information is not presented in the most captivating way. It is especially hard to like something when we do not understand why we are learning something, or why it’s important, or why we should care.

We also do not have to like every subject out there. Science is a branch of many subjects including Biology, Ecology, Chemistry, Physics, Zoology, Botany, Meteorology, Astronomy, and Social Sciences, to name a few. Individuals can contribute to society in their own field, ultimately working together.

Science is everywhere in real life- from the fuel for vehicles, the weather, medicine, electricity, sport, the internet, and even something simple like salt and water. When we add salt to water it increases the boiling point and decreases the freezing point. This means if you add salt to a pot of water it will take longer to boil, and if you live in a cold climate, adding salt means the water won’t freeze as quickly. You may have heard the expression “cooking is a science!”

Everything from your toothpaste, plastic, the fabrics in your clothes, is a product of science combined with other fields. Mixing baking soda and vinegar creates a chemical reaction that we use for cleaning surfaces and laundry. Even the act of breathing itself is a function of biology and science.

You may continue to “hate science” but hopefully this opens your mind to the way you benefit from or use science in your life every day.

The most important thing you can do is keep an open mind, ask questions like “How do we use science in real life” and when you come across statements that say “never” or “always” consider what exceptions there may be.

Check out Bill Nye the Science Guy if you want to see how nerding out about science can be fun, and help us understand real life!

dear paige,

i think you are ignorant, please consider what you are saying and dont group all of science into a single experience with a sucky experience

*into a hate towards that single entity derived from a sucky experience

I absolutely hate science it might be my teacher but it’s also the fact that we do like 5 min experiment that is anti-climatic and as stupid as putting salt in water and watching it dissolve (literally we did that) and we spent the rest of the time filling out forms and taking notes on everything! I hate science. Plus it’s not like we use science in real life.

Dear Paige,

I am not sure what grade you are in, but I can understand that sometimes information is not presented in the most captivating way. It is especially hard to like something when we do not understand why we are learning something, or why it’s important, or why we should care.

We also do not have to like every subject out there. Science is a branch of many subjects including Biology, Ecology, Chemistry, Physics, Zoology, Botany, Meteorology, Astronomy, and Social Sciences, to name a few. Individuals can contribute to society in their own field, ultimately working together.

Science is everywhere in real life- from the fuel for vehicles, the weather, medicine, electricity, sport, the internet, and even something simple like salt and water. When we add salt to water it increases the boiling point and decreases the freezing point. This means if you add salt to a pot of water it will take longer to boil, and if you live in a cold climate, adding salt means the water won’t freeze as quickly. You may have heard the expression “cooking is a science!”

Everything from your toothpaste, plastic, the fabrics in your clothes, is a product of science combined with other fields. Mixing baking soda and vinegar creates a chemical reaction that we use for cleaning surfaces and laundry. Even the act of breathing itself is a function of biology and science.

You may continue to “hate science” but hopefully this opens your mind to the way you benefit from or use science in your life every day.

The most important thing you can do is keep an open mind, ask questions like “How do we use science in real life” and when you come across statements that say “never” or “always” consider what exceptions there may be.

Check out Bill Nye the Science Guy if you want to see how nerding out about science can be fun, and help us understand real life!

dear paige,

i think you are ignorant, please consider what you are saying and dont group all of science into a single experience with a sucky experience

*into a hate towards that single entity derived from a sucky experience

I absolutely hate science it might be my teacher but it’s also the fact that we do like 5 min experiment that is anti-climatic and as stupid as putting salt in water and watching it dissolve (literally we did that) and we spent the rest of the time filling out forms and taking notes on everything! I hate science. Plus it’s not like we use science in real life.

Dear Paige,

I am not sure what grade you are in, but I can understand that sometimes information is not presented in the most captivating way. It is especially hard to like something when we do not understand why we are learning something, or why it’s important, or why we should care.

We also do not have to like every subject out there. Science is a branch of many subjects including Biology, Ecology, Chemistry, Physics, Zoology, Botany, Meteorology, Astronomy, and Social Sciences, to name a few. Individuals can contribute to society in their own field, ultimately working together.

Science is everywhere in real life- from the fuel for vehicles, the weather, medicine, electricity, sport, the internet, and even something simple like salt and water. When we add salt to water it increases the boiling point and decreases the freezing point. This means if you add salt to a pot of water it will take longer to boil, and if you live in a cold climate, adding salt means the water won’t freeze as quickly. You may have heard the expression “cooking is a science!”

Everything from your toothpaste, plastic, the fabrics in your clothes, is a product of science combined with other fields. Mixing baking soda and vinegar creates a chemical reaction that we use for cleaning surfaces and laundry. Even the act of breathing itself is a function of biology and science.

You may continue to “hate science” but hopefully this opens your mind to the way you benefit from or use science in your life every day.

The most important thing you can do is keep an open mind, ask questions like “How do we use science in real life” and when you come across statements that say “never” or “always” consider what exceptions there may be.

Check out Bill Nye the Science Guy if you want to see how nerding out about science can be fun, and help us understand real life!

dear paige,

i think you are ignorant, please consider what you are saying and dont group all of science into a single experience with a sucky experience

*into a hate towards that single entity derived from a sucky experience

I will tell you what I’VE learned: Haters are not happy people; they have to build themselves up by tearing others down. People who are always negatively gossiping about others should be avoided because they’ll do the same to you behind YOUR back. They can’t be trusted.

I will tell you what I’VE learned: Haters are not happy people; they have to build themselves up by tearing others down. People who are always negatively gossiping about others should be avoided because they’ll do the same to you behind YOUR back. They can’t be trusted.

I will tell you what I’VE learned: Haters are not happy people; they have to build themselves up by tearing others down. People who are always negatively gossiping about others should be avoided because they’ll do the same to you behind YOUR back. They can’t be trusted.

I will tell you what I’VE learned: Haters are not happy people; they have to build themselves up by tearing others down. People who are always negatively gossiping about others should be avoided because they’ll do the same to you behind YOUR back. They can’t be trusted.

I am currently dealing with a hater on a freaking social media app. #cyberbullying but I’m the winner. If you’re hated, take it, accept it, use it!!

I am currently dealing with a hater on a freaking social media app. #cyberbullying but I’m the winner. If you’re hated, take it, accept it, use it!!

I am currently dealing with a hater on a freaking social media app. #cyberbullying but I’m the winner. If you’re hated, take it, accept it, use it!!

I am currently dealing with a hater on a freaking social media app. #cyberbullying but I’m the winner. If you’re hated, take it, accept it, use it!!

Thank You So Much For This Insightful Truth. The World Is In Severe Defecit of Love & Understanding yet Has an Abundance Of Hate & Injustice. We The People Need To Take A Stand To Be Better Starting With Our Emotional Intelligence. Take A Good Look In The Mirror & Make That Change, Quite Literally-Become The Change You Want To See. CHOOSE LOVE OVER HATE, God Bless Us All.

Thank You So Much For This Insightful Truth. The World Is In Severe Defecit of Love & Understanding yet Has an Abundance Of Hate & Injustice. We The People Need To Take A Stand To Be Better Starting With Our Emotional Intelligence. Take A Good Look In The Mirror & Make That Change, Quite Literally-Become The Change You Want To See. CHOOSE LOVE OVER HATE, God Bless Us All.

Thank You So Much For This Insightful Truth. The World Is In Severe Defecit of Love & Understanding yet Has an Abundance Of Hate & Injustice. We The People Need To Take A Stand To Be Better Starting With Our Emotional Intelligence. Take A Good Look In The Mirror & Make That Change, Quite Literally-Become The Change You Want To See. CHOOSE LOVE OVER HATE, God Bless Us All.

Thank You So Much For This Insightful Truth. The World Is In Severe Defecit of Love & Understanding yet Has an Abundance Of Hate & Injustice. We The People Need To Take A Stand To Be Better Starting With Our Emotional Intelligence. Take A Good Look In The Mirror & Make That Change, Quite Literally-Become The Change You Want To See. CHOOSE LOVE OVER HATE, God Bless Us All.

I loved Sharon Russell’s perfect observation

I loved Sharon Russell’s perfect observation

I loved Sharon Russell’s perfect observation

I loved Sharon Russell’s perfect observation

Monique Kalinski is spot on Love is the only thing that will save the world and all it’s people but various ideologies put us all at odds with each other, even communists have rich and poor and none of the current mindsets work. I wish God would bless us all and open the minds of all people to achieve a common goal

Monique Kalinski is spot on Love is the only thing that will save the world and all it’s people but various ideologies put us all at odds with each other, even communists have rich and poor and none of the current mindsets work. I wish God would bless us all and open the minds of all people to achieve a common goal

Monique Kalinski is spot on Love is the only thing that will save the world and all it’s people but various ideologies put us all at odds with each other, even communists have rich and poor and none of the current mindsets work. I wish God would bless us all and open the minds of all people to achieve a common goal

Monique Kalinski is spot on Love is the only thing that will save the world and all it’s people but various ideologies put us all at odds with each other, even communists have rich and poor and none of the current mindsets work. I wish God would bless us all and open the minds of all people to achieve a common goal

It’s really good 👍 lesson it makes sense thanks

It’s really good 👍 lesson it makes sense thanks

It’s really good 👍 lesson it makes sense thanks

It’s really good 👍 lesson it makes sense thanks